By Niko Gómez with the support of Sori Fodor and Masa Nazzal / Pictures by Adam Bolt and No Name Kitchen Team in Bihać

I write this text after spending three months volunteering in Bihać (Bosnia and Herzegovina) with No Name Kitchen. I was in charge of the healthcare focal point with people on the move (PoM).

After three months of witnessing day after day how police forces and institutions exert all types of violence against people on the move who found themselves on the margins of the system, I write this text. From the more blatant violence, the one that you see in the borders, when the police release dogs on them, burn their possessions and force them to walk barefoot on the coals or strip them of their clothes, and force them to walk into the river’s freezing water.

To the more silent kind, the one enforced by the administration process, the waiting lists, the endless queues, to be minimized to a number.

Health facilities for people on the move in Bihać

Along with the testimonials that people on the move have shared, I’ve seen how Bosnian institutions operate within the health area: Camps where the showers and toilets, that 1500 people are using every day, are only cleaned once a day, with complete disregard for infectious diseases such as scabies, only being provided of one meal a day with barely any nutritional content, long queues to see the doctor of the camp, no mental health assistance provided. Public doctors that refuse to treat people with open wounds. People with infected wounds and even dog bites have to wait more than 12 hours for the ambulance to provide aid.

In short, people are faced with neglect and institutional violence.

I want to denounce the treatment people on the move have to endure in the refugee camps because neither my colleagues nor I think the camps provide any solution or support to the real issue.

My intention with this text is not to feed into the already existing stigma of associating people on the move with drugs. But rather, to start a discussion on how institutions operate under a welfare ideology that dehumanizes the individuals forced to live. That does not seek to improve quality of life but to do the minimum to keep them alive.

“Lyrica, what is that?”

When I first arrived here, not much time passed until I heard about Lyrica.

An Afghan guy asked if I had any, while treating his infected wounds. “Lyrica, what is that?” I asked, “It’s a pill… I need it to sleep, it helps me to relax”. I was surprised by the urgency in his voice and the anxiety with which he asked me. I offered him some relaxing tea, to teach him some breathwork that I use for my insomnia, and even the possibility to get mental health assistance from a licensed psychologist that No Name Kitchen offers as part of the program Care on the Move. However, the anxiety in which he asked worried me. It’s not the first time I’ve spoken with people who are addicted to psychotropics even though I’ve never heard of this specific one. I asked Alessia , the Health Technical Reference in No Name Kitchen.

Alessia explained to me that Lyrica (Pregabalin- active drug ingredient) is a medication used for epilepsy. But the effects it has can also calm the symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Some people in migratory transit use it and can generate heavy addiction problems. It can even cause overdose and death when combined with alcohol and other substances.

A few answers, but even more questions. “Where do they get it from?” – was one of the first things that came to my mind. These people are sleeping on the street, without resources or money, without the possibility of accessing medical care. It is a very hard medication, which requires a professional prescription. “What effects does it generate?” – Alessia explained to me that it has sedative and relaxing effects, as it reduces the pain signals that the damaged nerves send to the brain. However, we were told some people use it to go on game*. What was the point of taking it if it makes you sleepy and numb?”

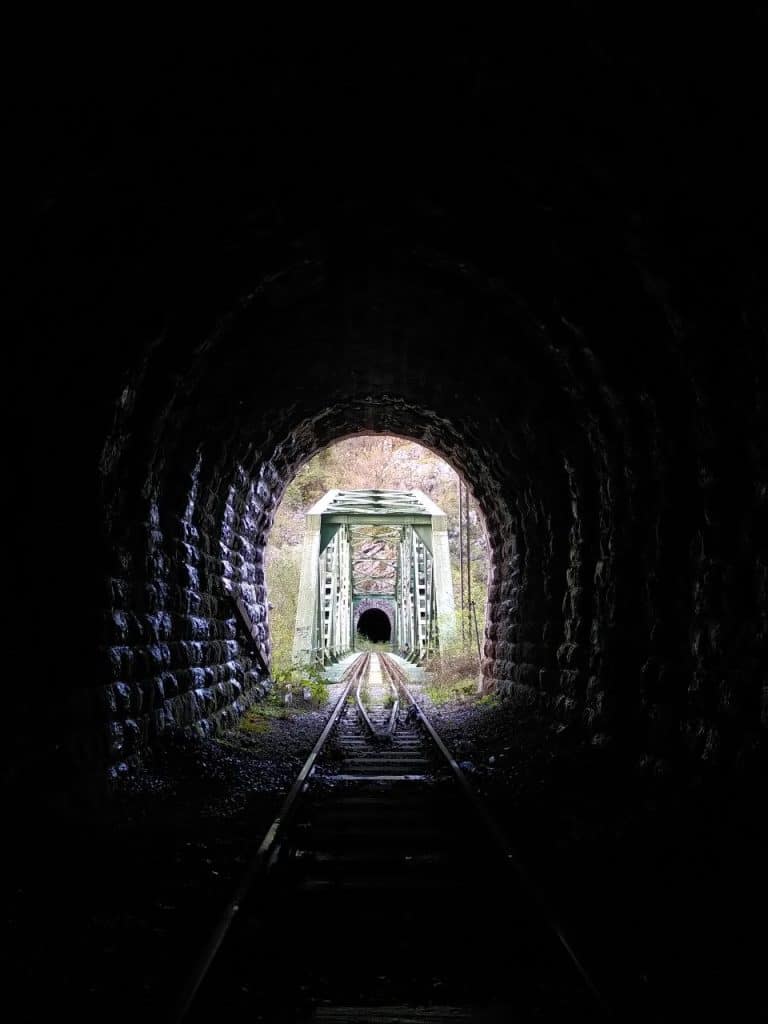

*Game is the term that People on the Move use to refer to the attempt to cross the border by walking through forests and rivers due to the lack of safe and legal pathways to reach the European Union. This is a life risking trip, as they are exposed to the elements, the lack of basic resources and the constant violence of police and military, which sometimes apply torture techniches in order to avoid people from crossing the borders. This procedures are known by the EU, and rather not stopped but reinforced by legislation, money and protocols.

The weeks go by and I’m starting to get used to hearing about Lyrica. I began to hear the stories of violence and stopped being surprised by substance use. As a team we try to set limits, we do not want people to consume in front of us nor are we going to provide them with alcohol or drugs, including psychotropic drugs. But in general, I don’t judge.

After listening to their life stories, hearing how messed up the trip is, how they face death again and again, the grief and sorrow… who am I to judge if it’s wrong or right to use substances for escapism? At this point, I’ve normalized it, until my new colleagues from the protection focal point arrive. In a conversation about the topic, they made me realize how important it is to talk about this issue. How important it is to break the stigma of “drug-addicted migrants” and put the focus elsewhere, on “the institutions that promote addiction.”

Finding the answers

My colleagues are incredible, they immediately got started to do interviews. We began to ask people on the move if they wanted to talk about the issue. And, to our surprise, they agreed enthusiastically. We found many people concerned, and aware of the problem behind the consumption of these substances. We began to find answers.

Most of the people we interviewed told us that they use, or have used, these drugs at some point during their travel.

When asked where they get them from, they respond that the doctor distributes them in Lipa Refugee Camp, the big camp here in Bihac.

In all the interviews the people tell us about the same modus operandi: Lyrica is distributed by the camp’s doctor after a short interview, where the only thing they ask about is if they have taken the drug before and the dose they need.

Personally, I am outraged. I have been a user of antidepressants and anxiolytics. I know first-hand the effects they can have on the body and how dangerous they can be if taken without psychological support. We asked: “Were you warned about the side effects before giving them to you? Did they ask you if you had addiction problems? Did they offer you any type of psychological support? Did they offer you any type of support to stop using it?” The answers were always negative.

The story changes a bit depending on who you ask, but in general the procedure is always the same, the doctor arrives, gives you the pill and then they forget about you. The people we asked explained to us that there are only a few doctors for 1,500 people in the Lipa camp. And “by giving the pills to people they ensure that the person is calm and does not cause problems”. An argument that responds to dehumanizing logics of control. However, many of them tell us that, even despite the freedom with which it is distributed, the dose is not enough.

Then they have to turn to other places to find it. And this is where we start to hear bizarre stories. Security guards who make extra money by distributing these pills, local people who work in pharmacies or hospitals who bring Lyrica to the outskirts of the countryside to sell it, other people on the move who get them from mafias… in short, a black market that takes advantage of the addiction of these people.

Lyrica is cheap. And it’s easy to get. M., one of the people we interviewed, told us:

“here anyone can get it, as long as they speak the language. If you go to a pharmacy and they don’t want to give it to you because you don’t have a prescription, you just have to go to another one and so on until you find one that sells it to you.”

M. also tells us that this methodology when distributing psychotropic drugs is repeated in other refugee camps where he has been, in Sarajevo or Serbia. Here we begin to wonder if it will be a pattern. We asked colleagues from the No Name Kitchen in Serbia. We are looking for information, we found some articles about people who investigated this before. Apparently is a common pattern in the institutions that work with people on the move.

Ok, we already know where they get it: through camp doctors, but especially through the black market. Now, why do they take it? What effects does it have?

Most people tell us about sedative effects and a feeling of euphoria. They tell us that some people take it before going to play the game since it has a numbing effect. You stop feeling the pain of the wounds you have experienced (from who knows how many push-backs. The term ‘pushback’ describes the unregulated cross-border expulsion of people on the move to another country) and, at the same time, you stop worrying about the trip. Fear, frustration, anxiety, remain numb. A., another boy we interviewed tells us about a feeling of euphoria that lasts about 7 hours.

But then comes the downturn, of course. And then they combine it with energy drinks or other types of stimulants. A cocktail for the body.

But it can’t be just that. When we talk to A., I begin to understand that the reasons behind addiction are much more complex. A. has been addicted to this substance for 8 years. He started consuming it in Algeria, when he was only 15 years old. He describes harsh living conditions in his country of origin. Poverty, lack of resources, homelessness, lack of support, etc. This makes me think. Yes, some begin the journey having previous addiction problems, but it is necessary to understand the circumstances in which they have grown up. And it is also necessary to understand these circumstances are the result of global policies that enrich a neocolonial Europe (and the West) at the expense of the exploitation of the countries of the global south. The same Europe that systematically expels them when they try to seek a better future within its borders.

The trauma and violence experienced are also factors worth highlighting when it comes to drug use on migratory routes. Marina is our care supporter in NNK (she is in charge of the emotional support of the volunteers team). She is an educator and training to be a trauma counselor. In a meeting with her about the connection between drug use and trauma, she explains to us that one of the possible reasons why people who have experienced traumatic experiences are using drugs is because it can alleviate the effects of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). The flashes, the stress, the hypervigilance… it becomes easier if you cover it through consumption.

I think the hardest thing we have heard in these interviews is when we ask A. if he has known someone who died of an overdose and the answer is affirmative. Still, he continues to consume. Just a few months ago a friend of a previous kitchen team died in Velika Kladuša. His death, as one of many others, is the responsibility of European institutions that systematically allows people to die on the borders.

Conclusions after the interviews and research

Things are starting to make more sense. We still have many things to investigate. We want to ask underage people if the same pattern is also repeated within the Borići camp, we want to talk to people who would not have used Lyrica before starting the trip. But I have to leave soon. For now, from this little research from the activities from the field and based on individual interviews, we can extract:

1. Within the Lipa refugee camp, psychopharmacological medication is being distributed without follow-up or pertinent indications by health professionals.

2. That, parallel to this situation, a black market for the same medication operates, in which locals, mafias and people on the move participate.

3. That the institutions are aware of this situation but refuse to offer treatments that solve the addiction problems of the people who are protected under their guardianship.

4. That this seems not an isolated case, but rather a common methodology to other EU countries.

And we seek, therefore, to denounce this situation as an example of bad practices and institutional abandonment that add another drop to the harsh reality that, to this corrupt Europe migrant lives do not matter.

I hope this can serve as a testimony to the types of violence that are not visible.

And I also hope that it can bring a little clarity and empathy towards the delicate issue of substance use in migratory transits, about which so little is talked about for fear of stigma.