Article by Nina Olivieri as part of No Name Kitchen Team in Bihac

It’s not difficult to find empty or wary looks when meeting People on the Move around Bihac, Bosnia I Herzegovina. It’s often easy to walk around them; you get used to the necessary critical distance in solidarity. Then, there are times in which you spend more time with a group of people, and it becomes impossible not to realize that everyone’s destinies and lives are so intertwined; so different and so similar.

Our team in Bihac had the opportunity of meeting and spending time with four amazing people, who became our friends in just the blink of an eye. We first encountered L. and I. , two young men from China, during a walk along the river, and as it often happens, we stopped by the bench where they were sitting to ask whether they needed any clothes or food. From then on, the whole team spent every free moment with them, and created a precious bond.

The initial approaches between the team, L. and I. are mainly focused on distributing clothes and food. But from the beginning we started to take our time and enjoy conversation, leading to the moment in which they took us to the squat where they are spending the nights. They walk us through an enormous set of connected buildings, passing through hidden passages, staircases, broken doors, avoiding the dangerous holes on the ground, big enough to break a leg. Everything is full of holes; the rain that is haunting the city this week is coming through from all parts, creating little (or not so little) rivers of dirt flowing all around. The smell that exhales from the running water and the proximity to the river creates an extremely humid and unsanitary environment.

On the last floor, L. and I. set up their newly received sleeping bags and mats. They are staying in a small and very dusty room together with two other Chinese guys, Lu. and To. the walls are full of openings that were surely supposed to become windows at some point of the building’s life, and in the same way no entrance ever received a door to close it with. The first time our team goes to bring some food it’s because L. and I. warn us about the conditions of extreme fatigue endured by their friends. In fact, when we enter the room, they barely have the energy to lift up their heads and have a look at the food that we brought. For this reason, we leave everything there and decide to come back after they had their well-deserved rest.

We go back later in the evening. This time Lu. And To. are awake, and after having shared a couple of burek’s and iced teas, they feel comfortable enough to share their experiences. The previous night they had gone “game”, meaning they tried to cross the border between Bosnia i Herzegovina and Croatia, the last border before the European Union. “Game” is the term that people on the move use to refer the attempt to cross the border by walking through forests and dangerous rivers due to the lack of safe and legal pathways to reach the European Union.

“Game” is the term that people on the move use to refer the attempt to cross the border by walking through forests and dangerous rivers for days due to the lack of safe and legal pathways to reach the European Union.

They tell us about the unpleasant, to say the least, encounter with the Croatian border police: unsurprisingly it’s a story about violent prevarication and power abuse. During the pushback all of their belongings were confiscated, but shockingly also the most precious of them all: the passport. In today’s world, where nation-state belonging is everything: to move, to work, to exist.. what is left without a passport?

In today’s world, where nation-state belonging is everything: to move, to work, to exist.. what is left without a passport?

These are the questions that To. asks himself. He appears to be mostly angry, but then starts sharing about his life. He’s 26 years old, and back in China he owned a coffee shop. His dream has always been to work with people, give them hospitality, and possibly in the future open a hostel as well. Unfortunately, his business was not going well, debts started to pile up, and during the COVID-19 outbreak his shop was closed. To. didn’t agree with the strong provisions taken by the government, and he decided to share his disapproval on social media. Not long after this, the police showed up at his house and brought him to prison, where he spent a few days. Considering his financial situation, he decided to leave the country to go to Belgrade, Serbia, where he could easily get to with a VISA, to then continue his journey to Europe. To. wants to arrive in Germany and fulfill his dream of opening a coffee shop/hostel, where he invited all of us to visit him. This is when his attitude changes. When he’s talking about his journey, or the experience with the border police, he appears strong and motivated. On the contrary, as soon as we start speaking about his dreams, a clear weight appears on his body. His posture changes; shoulders bend, eyes water, knees start to look difficult to sustain. He becomes silent and looks at the ground.

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony nr. 2 is playing in L. ‘s head while we talk. He thinks about it constantly, he told me, because that’s where he gets the strength to keep walking. The intensity of this music resonates between the walls . L. is 25 years old, but he looks way younger. He has a naïvely happy smile; we talk about music and movies, but he doesn’t seem particularly open to talk about his past. In particular, he doesn’t tell us about why he escaped China. He only keeps on telling that To.’s situation is worse, deviating the attention from himself and minimizing his own personal experience.

At the same time, I. is listening from afar. He’s the only one that remains serious the whole night. He only tells us that he left his country because he was arrested and put in prison for 15 days after having shared on social media negative comments about the Chinese government. He seems wary at the beginning, but with time I understand that the events of the previous night profoundly touched him. He is traveling with L., and their plan was to “go game” the next day, but after hearing what happened to To. and Lu., their plans changed. The chance of getting their passports stolen seems to them the worst thing that can happen. They share To’s view on the role of the passport as a defining tool to access a dignifying future. Now their decision is to go back to Serbia to find a job in a restaurant and put some money aside, while waiting to understand what the best next move is.

When the light starts retrieving from the open “windows” our friends pack their belongings to go in the direction of Lipa Camp, the Temporary Reception Center for single males located 23 km from the center of Bihac. They want to spend a couple of nights there in order to rest in a proper bed, take a shower and recharge before leaving town and continuing their journey. All except Lu.; he doesn’t speak English, but the others translate for us. He was pushed-back together with To., and from that moment on, Lu.’s priority has been finding a new phone to get in contact with his family. He doesn’t care about a comfy bed, warmth or the company of the rest of the group; his mind is set on a precise goal. The team then separates from him and walks with L., To. and I. to the bus station, where a taxi takes them to Lipa Camp. We hug, say goodbye and promise each other to keep in touch.

In the late morning of the following day, some members of our team pass in front of the abandoned building and notice their bags on a bench. We then find L., To. and I. resting again on the grass close to the river. We stop to understand what is going on, and they explain to us the situation. I. is the most mature of the three, and often speaks for the others when there are serious matters to be discussed. This time he tells us that, while they spent a night in Lipa Camp, it was made clear from the beginning that they could not stay there. That very morning, they were called to the attention of a camp official who told them that they could either leave the premises of the camp or the police would have them deported back to China. The three were extremely confused, disappointed and angry by this announcement. When we speak about it, they are not very sure of the reason why they were refused to stay in the camp, and honestly none of us on the team has a clear answer for this.

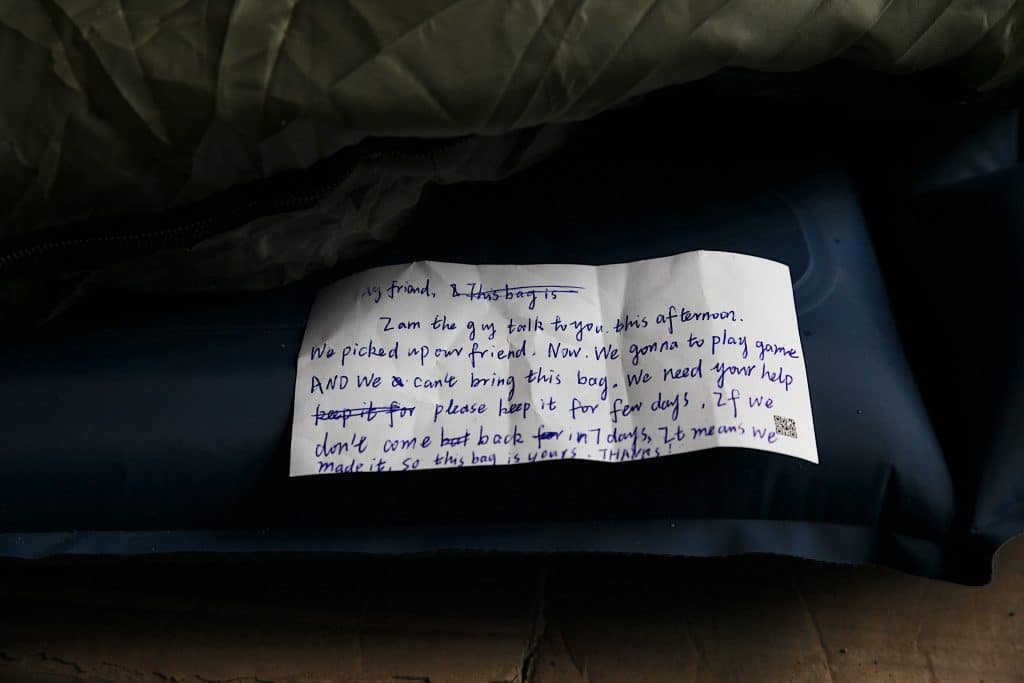

In the following days we keep coming back to the squat. We know that our time together is limited, so we pass by 2 or 3 times a day, just to spend time with our friends. We have a pizza all together, go to the river to have a pic-nic and a swim. Then, on the fourth day, To. tells us that he’s going to leave at that precise moment together with Lu., to try and cross again. Now he is in Italy, continuing his journey. We still text daily and give each other energy. This is how I know that him and all the others have lost contact with Lu. while he was chased by police in trying to cross the border to Croatia. In the meantime, I. and L. decided to test their luck and “go game”; they are now in Croatia.

This short but powerful meeting pushed our team in Bihac to take a moment to reflect all together on our condition, and the condition of all the People on the Move we meet daily. Our work, which is sometimes chaotic and doesn’t leave us a lot of time to stop and connect with people, leads to the creation of some sort of distancing. This is of course also necessary to keep the work going, without feeling overwhelmed by the experiences we are surrounded with and by our resonating privilege. At the same time, the friendship with To., Lu, L. and I. led us to make a lot of comparisons with our friends’ and our own lives. The injustices that these very young people, that could be every single one of us, have to go through daily are astonishing. Moreover, it’s impossible not to think about the responsibility that can be appointed to the European Union, to its fund management, to its securitarian policies. How is it possible that these policies enforced by the EU, which declares itself to be a leader of progress and human rights, bring upon a system that allows police forces to have so much individual power? To decide whether or not to deny a future to another human being?

How is it possible that these policies enforced by the EU, which declares itself to be a leader of progress and human rights, bring upon a system that allows police forces to have so much individual power? To decide whether or not to deny a future to another human being?