Written by Seyma Saylak and Joe Boon as part of No Name Kitchen in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photos by Joe Boon

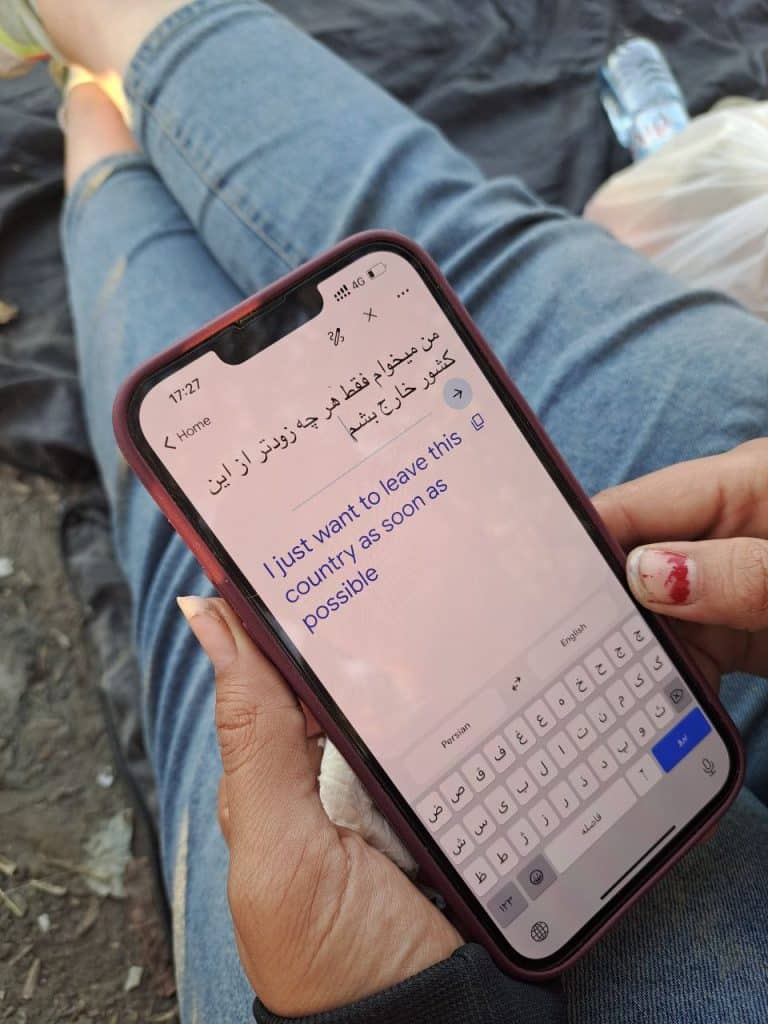

A young Kurdish man U., sits on a bench in the Bihać bus station. It is clear from his eyes, from his voice, from his words how tired he is, how traumatised and frustrated he is. His voice shakes while he says:

“We were left alone in a hut in the middle of a forest. We didn’t eat anything for three days. We only had cigarettes. I was about to eat a cigarette. On the third day, we felt faint, delusional with stomach pain. We thought we were going to die.”

A group of 15 young Turkish and Kurdish men from Turkey explained to us how they crossed the Croatian border the night before after walking for 9 hours in the forest. This was the first time they’d done it for most of them, as they explained. They said they had to pay a large sum of money to smuggler as they did not have the knowledge and experience to survive in the Balkan towns, mountains and forests that they had never been to before.

As there are no safe and legal ways to migrate, people find themselves in these hard situation, in which they often need to put their future in the hands of someone else, because they cannot simply cross to a new country to ask for asylum/international protection. They explained afterwards how, as promised, two smugglers were guiding them along the border crossing. They continued to walk for 3 hours through very rough terrain.

U. describes the mountains they had to climb full of fear and awe. He told us that when night fell, people were forced to enter a tiny hut in the middle of nowhere. They were robbed of the last money they had and left stranded in the middle of nowhere by the smugglers. They spent two days of despair in this hut.

The lack of safe passage for migrate puts people in extremely vulnerable situations

This is a part of the reality of the border zone we cannot and must not turn away from. The reality at the externalised borders of Europe, where people in transit find themselves prey to smuggling networks. How we look at this reality is critical, we must not to lose sight of the actual perpetrators of violence in this area, Europe and beyond. Intense smuggling activity, which is one of the distinctive characteristics of the borders when they are closed with no legal and safe paths to migrate, is a direct outcome of the border regime of Fortress Europe, whilst not providing any legal or safe pathways for people on the move into Europe.

By the third day, U. and his friends’ physical strength was dwindling due to exhaustion from starvation, as U. explained to us later, when we met in the city of Bihać. They decided that there was no other solution but to hand themselves over to the Croatian police, although they didn’t have a number or even signal to call. So they started to walk again for four kilometres with the hope of encountering border police. This irony made U. smile involuntarily. The irony that on game (the word many people use for the act of crossing borders) where the only rule is not to get caught by the police ends with a desperate search for the police.

Finally, according to the story shared to us, a pair of Croatian police, a man and a woman, came across them and U. asked them for help. They didn’t face any direct physical violence from these officers after they said they were from Turkey, U. thinks his Turkish nationality is the reason they spared him brutality, and this could be true when referring to other stories. However, the police didn’t give any food or water to the people whilst enjoying their coffee in the police car. After putting the people in a police van, they drove to the border and pushed them back into Bosnian territory. Just as a reminder: these people did not experience physical violence, but their pushbacks are illegal.

Structural violence

This is just one of the many stories where people on the move have found themselves in perilous and vulnerable situations at the border zone. The structural violence of European Union countries expands way beyond its borders, it has different facets and practices at the border zone and is rooted in racial and cultural violence. We know from the testimonies of the people we’ve met that there is no one single experience of being on the move. The border regime itself is racialised and ableist as well as biased in regards to skin colour, country of origin, gender, sexuality, economic and physical condition.

There is a crystallising reality on the western Balkan borders (and on closed borders in general), people trying to survive in dire conditions have to rely on smuggling structures. For decades, the EU has been trying to imbue this reality with policy instruments and narratives. When we look at the current policy documents including the Action Plan for Western Balkans adopted in 2022, the New Pact on Migration and Asylum agreed in 2023, alongside reports of the EU and Balkan countries constantly emphasising the fight against smuggling and organised crime in order to reduce irregular migration. This discourse provides both the EU and its external border countries with a legitimised basis for criminalising people’s freedom of movement, and impeding solidarity efforts.

In reality, people only put their lives in the hands of smugglers when they do not have the right to move freely. Why would anyone pay thousands of euros to a smuggling group, if they could pay some money for a plane ticket or a bus to move to another country? So the European Union’s border policies only make those groups stronger.

After being pushed back, U. and his friends had the chance to eat only after walking for hours again and eventually reaching Bihac. He clearly stated that he is physically and mentally wounded, and asks aloud how he will find the courage, money, and physical strength to try again. There was no response or voice around him to answer.