Text and photos by Ginevra Canessa

A nice summer breeze is blowing as we sit under a tree with two friends. We are surrounded by green hills, singing birds and the mild early morning temperatures accompany our chat. It is an idyllic scene from the outside. Yet, our conversation deeply clashes with the tranquility surrounding us and the reality that the two friends describe to us is filled with violence and broken dreams. They have fled their country, for different reasons, and they have been on the move for many years.

For their opposition to their government, they have both been subject to months of torture, which have inevitably affected their physical and mental health. Even now, their suffering has not ended, and neither has their search for a place where their fundamental human rights will be respected.

Our friends currently live in Bosnia-Herzegovina and our meeting takes place in the proximity of Lipa Camp, the new Temporary Reception Center (TRC) inaugurated in the Una Sana Canton district in 2021 (after the fire that destroyed the previous one). With a sharp increase in the number of the transit community, from 2018 Bosnia has become one of the main recipients of EU funds for the outsourcing of migration management to non-EU countries. It is indeed the case that the camp is managed in a joint effort between the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) and the Service for Foreigners’ Affairs (SFA), a branch of the Bosnian Ministry of Security.

Functioning according to logics of profit, the camp benefits from the expansion of people on the move who are detained there. This logic is well reflected also in the language used by IOM personnel. People on the move are indeed referred to as “customers” and the buses that transport pushbacked people are defined as a “shuttle bus service”.

The EU and funding partners have been allocating increasing financial resources in Bosnia-Herzegovina for the construction and development of a site that degrades the lives of people who are migrating, whilst restricting their rights to movement for their claim of asylum. Whilst the EU remains the main contributor, Lipa Camp also recieves fundings from the German Federal Agency for Technical Relief, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Interior, the Austrian Development Agency, the Swiss Government, the Vatican, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation and the Council of Europe. Despite the high amount of money invested into it, however, residents at Lipa continue to lack the most fundamental services for a life with dignity.

As part of the prison-industrial complex (PIX), Lipa camp exists for the economic interests of governments and private companies, but most of all for the maintenance of the racial borders of Fortress Europe. Widespread allegations point to the fact that the more people reside in the camp, the higher the financial gains for Lipa’s management, which since 2021 has passed under the control of the Service for Foreigner’s Affair (SFA).

The increased number of evictions from squats, taking place in the immediate aftermath of Lipa’s opening in November 2021, might indeed point to the validity of this claim. Notably, on May 2021, the eviction of Dom Penzionera, a former abandoned nursing home in Bihac hosting at the time around 250 POMs, resulted in their immediate transportation into the camp. As of today, when people get evicted from squats in Bihac they are forcefully moved into Lipa or Borici camps. Further investigations remain necessary to have a more encompassing understanding of Lipa Camp’s management.

In regard to our current understanding, however, it remains that the several forms of violence that are perpetrated within its fences are in direct contrast to the liberal self-representation of the EU as protector of human rights and fundamental liberties. The words and lived experiences of those who are constrained there provide evidence to this claim.

Testimonies

“Let them hear our voice” says our friend before starting to describe the degrading conditions of the camp. He has been living in Lipa since last winter due to poor health conditions and lack of money. The Croatian police violently pushbacked him six months ago after a border crossing attempt. The beatings and humiliation that he received further worsened his mental and physical capacities, which were already challenged by months of torture in his country of origin and the journey to Bihac.

He tells us that for nine months he has been suffering from the following: migraine, depression, anxiety, hyperactive thyroid, genital infections, prostate inflammation, and insomnia. The medical facilities in the camp have not alleviated his sufferings. In contrast, he describes having often been treated in a very rude way by doctors who, in the majority of cases, prescribe paracetamol tablets for all kinds of pain.

Located 25 km from the center of Bihac, the camp represents one of the main points of arrival for people who are pushbacked at the Croatian border. Having already experienced forms of violence and humiliation in their travel to Europe, the Bosnian- Croatian border represents for many the hardest step to enter EU countries.

Over the years, Croatian police seems to have developed more and more strategies to increase the suffering and the lived traumas of people on the move. In most cases, phones get stolen or destroyed by the police, alongside with clothes and money. On more occasions, people have reported being taken shoes and being given smaller sizes on purpose, resulting often in feet and legs injuries. It is also common practice for the police to violently beat, sexually humiliate and, in some cases, rape people. For sexual minorities, as much research has already pointed out, border violence is often much harsher.

Lipa’s remote location, in the middle of the Bosnian countryside, is not by chance and reflects the segregatory intentions of its management and the local administration. Public spaces in Bihac have been sites of violent discrimination against people on the move, with police officers shouting at people that it is forbidden for them to stay in the city center, to play football in the park, or to smoke a cigarette on a bench. Lipa camp becomes then the ultimate segregatory space where POMs disappear from the sight of locals to inhabit a reality of temporal uncertainty in which forms of invisible violence are regularly perpetrated.

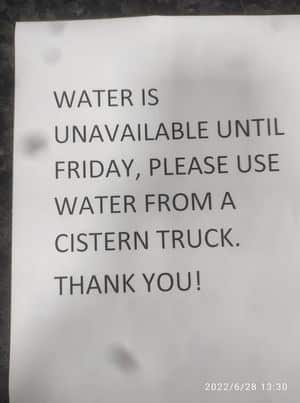

The remoteness of the camp makes it so that residents at Lipa have to walk for seven hours to reach shops and services. This move becomes necessary given the negligent distribution of clothes and food at the camp. For the entirety of last week, it became necessary also to access running water as the camp announced on July 28th that the latter would be temporarily unavailable. Residents have reported that toilet and shower facilities did not work from Monday until Friday.

The only water available, both for cleaning purposes and drinking, was delivered by a cistern truck. As temperatures reached peaks of 37° in the Una Sana Canton, residents at Lipa Camp had rationed drinking water and could not shower nor flush toilets. “It’s really hot here, concrete and metal Lipa, literally hell” our friend tells us in his description of those days. Lipa camp consists of a cement site, surrounded by barbed wire and organised in containers with six beds each. The lack of running water, combined with the already harsh living conditions, has further degraded the lives of people at Lipa camp.

This suspension of fundamental services, however, does not represent an isolated catastrophe and simply adds up to the general issue here which is the existence of the camp itself. As a site to restrict the freedom of movement of many people, as well as to violate their fundamental rights, Lipa camp effectively detains and divides people.

As the camp is exclusively populated by single men, older than eighteen years old, families who arrive in Bihac are generally split between Lipa and Borici Camp, the designated location for women and minors. As in the case of a group of two brothers and one sister from Sub-Saharan Africa, this division has resulted in the older sibling having to stay in Lipa. The three haven’t seen each other for more than a month.

Many people have reported being treated as prisoners. Apart from breakfast, people complain about food which mainly consists of rice and bread, thus lacking the necessary nutritious properties for a healthy diet. Kitchens are available for use and internal NGOs provide, at times, fresh food for residents to cook. This does not change the fact that many suffer from intestinal problems and hemorrhoids pointing again to the degrading living conditions of the camp. These are also confirmed by the protests, including hunger strikes, that residents at Lipa have conducted in these years.

In addition to this, the prison-like setting of Lipa is reinforced by the climate of discipline and punishment enforced by police functionaries. Acts of physical violence against residents are in fact the nor, according to different testimonies, and only add up to previous traumas. Our friend shares with us one episode in which a person with mental disabilities started screaming whilst queuing for food. Police went over to him and started slapping him in front of everyone. This climate of terror is also heightened by the entrance to the camp for residents. People have to show their IDs to police officers who sit in a cabin with blacked-out windows: whilst the camp functionary can see who is entering the camp, the resident cannot, adding up to a general sensation of surveillance. The latter is also emphasised by the 10 pm curfew, which despite the remoteness of the camp, continues to be enforced by camp authorities to reproduce forms of discipline and social control, ultimately restricting their freedom of movement.

When life is denied

Not only have the lives of people in Lipa been stripped off their fundamental human rights but their biological life has also been rendered disposable. Philosopher Achille Mbembe coined the concept of “necropolitics” to describe the political structures of power that led to the emergence of social conditions condemning large populations to the status of “living dead”. This kind of logic is explicit in the treatment of people on the move in camps, in the segregatory policies denying their access to the center of Bihac, and in the violent pushbacks and torture that they endure on the Croatian border at the hands of police divisions who are directly financed with EU money.

The concept of necropolitics is thus essential to understand that these strategies are not aimed at the mere exclusion of a population for the maintenance of concentrated wealth. European governments are effectively deploying practices that implicitly or not aim at killing off an unwanted community in transit. The voices of people on the move, however, cannot be silenced.

The nationalities and names of the people interviewed have not been stated due to the risk they incur within camps in the case their identities are revealed.