By Mirka del Pasqua, as part of No Name Kitchen Team in Bihać. English edited by Bethany

We publish the first-person narration of a volunteer and activist in Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina, who’ fights ‘s been, together with people on the move, against an unjust and discriminatory system, where health, a fundamental right of individuals, is denied.

NNK with its health on the move project wants to promote universal access to health care and denounce situations of denied access, as this story shows.

- “Sorry, if we accept this guy here, we have first to call the police.”

- “Does he speak arab? We cannot help him.”

- ”Do you really trust to all the diseases he invents”

These are just a few answers that we have received whist we try to help People on the Move with their health needs. Someone may wonder what it means to support migrants in receiving basic health care.

This question is understandable because in a normal society, there wouldn’t be a need of this kind of assistance, but the truth is that apparently, they are not part of a normal society, and very often, their basic health rights are denied.

It’s a late afternoon when we bring S. (we hide his name at his request) to the emergency hospital.

After the Croatian police kicked his face with iron boots whilst at the border last night, he lost 4 teeth, and his face was completely smashed in. He explained that when he saw the border police officers, he just kneeled on the ground, raising his hands, aware that he would be pushed back, and nothing more could have been done.

He would have tried his luck next time, as he used to say. But this time, kneeling with hands held up wasn’t enough. The policemen approached him, pointing their torches directly in his eyes. Blinded by the light, he couldn’t see their faces, but he felt every kick he received throughout his body. They laughed, and he believed in that moment, they would have killed him.

At the desk of the emergency hospital, the lady repeats the same sentence: “Before assessing him, we have to call the police because he has been assulted.”

It’s very ironic, as he has been assaulted by the police! Im standing at the desk shocked and unimpressed at the level of care he is receiving. I think, I will not move, they can even call the police. The important thing is that S. receives his treatment.

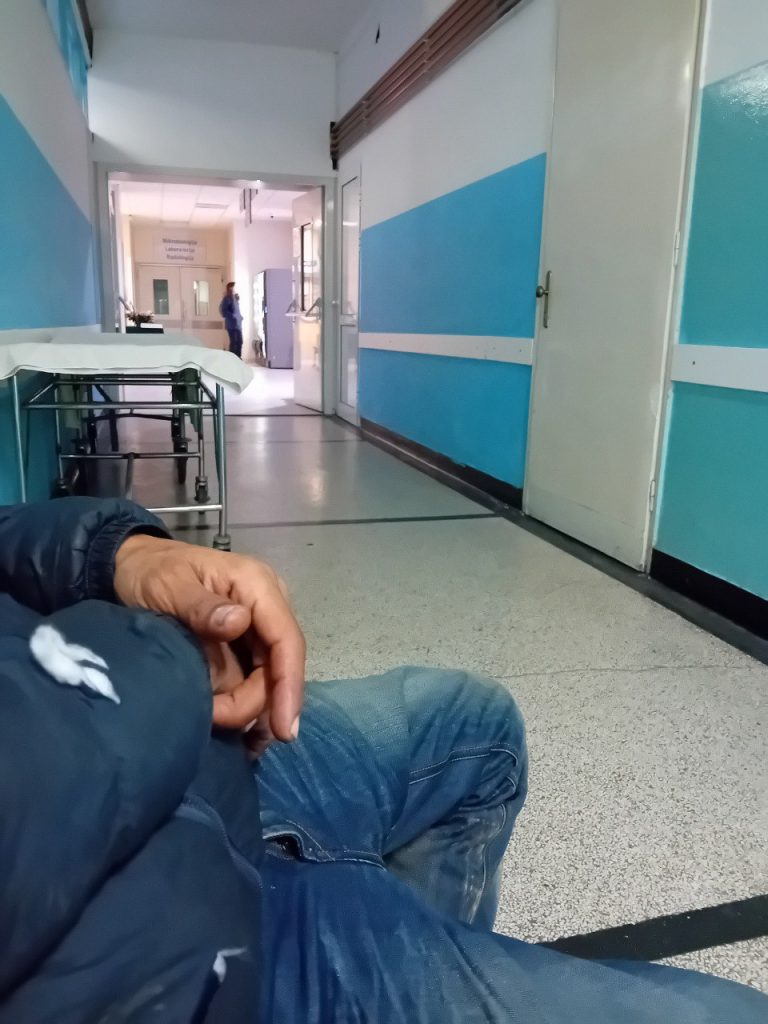

He is so weak and shaken that he can not even stand, exhausted, falling asleep at his chair.

The lady doesn’t expect this reaction, whilst she continues to talk and repeats the word police a few times, I stand my ground. In the end, she calls someone who gives a quick visit to S. and declares that he needs to go to the hospital for an X-ray. S. falls again asleep on the bed, he is exhausted, and the pain is unbearable without medicines. I see an ambulance parked, and I ask if they can bring him to the hospital, just 2 km from there. No, the ambulance is for emergencies: S, who has been kicked on the ground in his face, losing 4 teeth, then managed to walk back with the last of his energy only to be abandoned on a chair losing consciousness from the pain, and to be told it is not an emergency….

We call a taxi, aware that it will be a long night. We arrive at the hospital, where they make us wait in line for the generic visit, with our x-ray request from the emergency hospital. I count 4 people in front of us, I count them because something tells me that soon there will be more in front of us. People come and go out of the room with the doctor calling for the next person, with more people arriving and waiting in line. Time goes by, S. falls asleep again on the chair, sometimes moaning for the pain.

As I suspected, when it was our turn to be called, the people who arrived after us began to be called for. But I cannot say if these are emergencies or not. I will not talk about the exhausting hours of waiting, about the false promises of the doctors that our turn would soon come. Its when I see a woman with a cut on her finger passing before us, I finally knock at the door, asking what is the problem because it’s clear that not all these people are not in a more serious condition than S.

Finally, they let us in, and one nurse laughs at S. because of his face condition and because “he stinks”, and they send us to the x-ray room. After just 5 hours of waiting S. is so exhausted that he doesn’t even want to wait to go to a pharmacy and buy his medicine, he just wants to lie down somewhere and not to see a hospital anymore.

But S. can consider himself lucky.

Having epilepsy at the European Borders

A., has epilepsy. Devloped as a tennager and has not seen a neurologist or a specialist doctor yet. After many doors closed by the public health system, we tried to contact a private clinic because havung had three crises already, he really needed his medication. He couldn’t run the risk of having another one, especially in this harsh environment, the street life. He couldn’t run the risk with his health.

The first clinic simply did not accept the call because I was speaking English, and they were not able to understand me. The second one didn’t seem to have problems with the English language, but with A.’s full name.

” Does he speak Arab? Sorry, we can’t help him. We don’t have a translator”.

It sounded like an excuse because when I said that I could provide a translator, they didn’t let me have an appointment… The third clinic looked very kind, and sometimes it’s even worse to be rejected with kindness: the lady told me that the doctor was very busy, and he would have checked on his agenda and called me back to communicate the date of the appointment.

A and me are still waiting…. But some don’t even wait.

“First we call the police”

M., an individual with two deep cuts on his head tried to get stitches, and was so afraid when the personnel at the emergency hospital told him that they would have first called the police that he got out without receiving any treatment, relying on us who at least try and keep his wounds clean. M. lived in one of the squats spread around the city, not exactly the right place to stay with two deep open wounds. It was very hard to keep the wounds clean every day, but luckily, now M. is fine, and after one month, his wounds are closed.

These are just a few examples of what we can call” institutional violence”.

We can’t call it differently because, making the way difficult for a person to have access to medical treatment or to deny basic health rights is definitely a form of violence. Life on the Balkan route is so hard that people often don’t even try to assert their health rights and just give up.

But if they give up, we don’t.

And we keep on supporting them, listening to their needs, taking our time to go to hospitals and clinics to arrange appointments, to avoid discriminatory behaviours or threats, to make sure that they will be visited, and they will receive the treatments that they need. And, of course, denouncing this form of violence because health rights have no colour or country of origin. Health is a basic human right.