By Joe Boon and Seyma Saylak as part of No Name Kitchen team in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Main Photo Hannah Parry

Every two weeks we try to set up portable showers for our friends who are on the move. We lug water canisters, a homemade portable shower unit, batteries, a tent for privacy, towels, blankets for hanging out on whilst waiting your turn to shower and hygiene products including razors and shower gel to offer people the chance to exercise some self-care and rejuvenation. Many of our friends live in precarious environments, makeshift homes in abandoned and dilapidated buildings, with no facilities to clean or wash.

Where we set up our shower is usually a field in the centre of the city, there’s a lot of litter and the smell from people using the space as a toilet is prevalent once the shower starts. But this environment offers us some privacy amongst the tall grass and shrubbery.

Last time we did the showers we met W. from China. He didn’t want to shower, only to help us collect the rubbish into bin bags to make the area more appealing for our friends who wanted to shower. He assisted us with some technical difficulties we were having with the boiler, telling us via our phone’s translator, that he used to work with boilers back home. From the moment we met W. he had a smile from ear to ear and was always friendly.

After we’d packed up the showers and were going to our usual spot to talk to some more people on the move, W. hung around and shared his story and experiences with us. He had come to Bosnia recently and was looking for a different, freer life in Europe. All W. wanted was some food and did not request clothing. As the sun began to set over the mountains of Bihać, he expressed to us that he was worried about the Croatian border police, he was aware of the way they beat people and stole their money and possessions. He asked if we could look after some money for him as he heard that if the police caught him at the border they would steal it. For many reasons, we could not help him in this way, but he was very understanding and friendship pressed on.

Scaping China to face violence in Europe

The next time we saw W. he was at the bus station with another Chinese man T. He introduced me and told me that T. had been caught on the Croatian side of the border. He said, “They released dogs on him but luckily the dogs had only bitten clothing and not skin.” T. later showed me where they’d smacked him on the arm with a baton. The Croatian police stole his money and his phone.

He was only 27 years old and had arrived in Bosnia 5 days before his first attempt to cross into the EU. A doctor supporting our team checked his arm for breakage and bandaged him up for security. W. looked after T. whilst they were together in Bihać, two strangers helping and caring for each other as friends – this is common in the field.

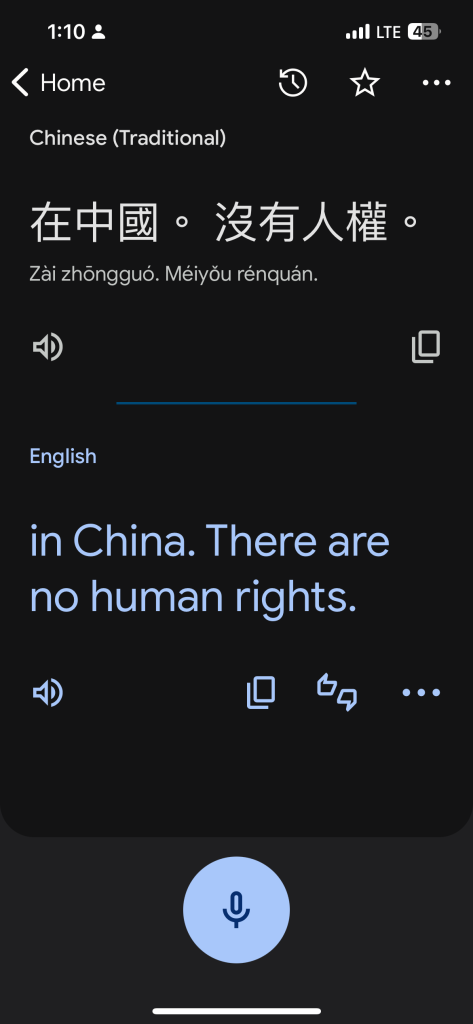

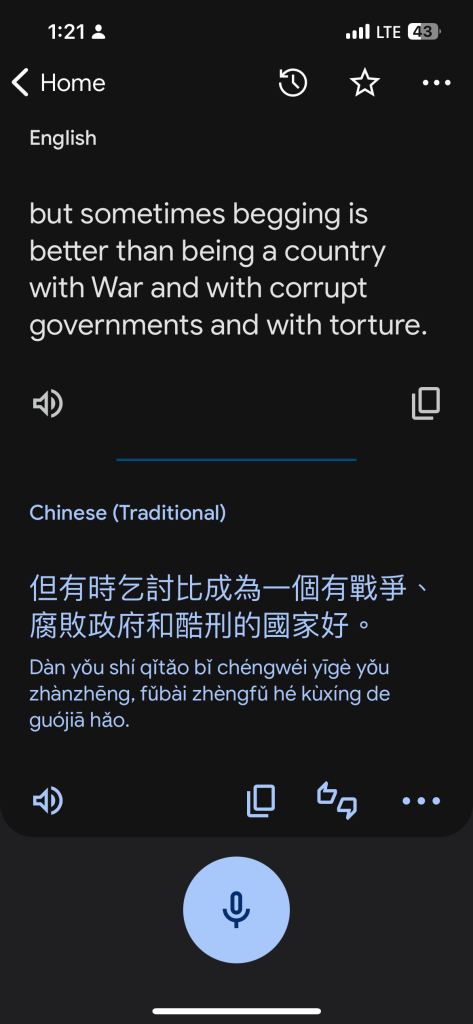

W. was speaking to us about why he left China and showed a message on the translator that read “In China there are no human rights.” W. wants to be able to speak freely and live without persecution where he is. The next message W. showed me on the translator read “In Croatia no human rights either.” Later W. asked me about what happens to people when they arrive in Europe and that he’d heard some people end up begging for money. He asked why. I said, “Because for some people begging for money is better than being somewhere surrounded by war, a corrupt government, or torture.” He laughed and said, “I’m going to Europe to beg?!” This idea made him laugh very hard. Sometimes all you can do is laugh.

Through meeting different people in the field and hearing their stories we learn a lot. Our conversations highlight how being on the move can vary massively between communities. Even though there is a commonality in facing the systemic violence of the EU border regime, different communities experience things differently. For instance, while Syrians and Afghans who’ve been using the Balkan route for almost a decade have woven a dense and transnational web of knowledge and experience over time, communities like the Chinese and Nepalese might find it tougher to tap into a solidarity network. They can become more clandestine and imperceptible, which can be a double-edged sword, sometimes working for them and sometimes against them.

Driven by a mix of curiosity and a desire to understand W.’s story better, as well as to investigate if there was a local support network for our friends in the city, we decided to go to three Chinese shops in town. It was impromptu, and our heads were buzzing with questions. What were we going to ask the Chinese owners? How would we approach them and what would they say?

After meeting the shop owners, we started to look at things differently. To overcome borders for some groups it is harder than for others, and the path of interaction more winding. But stepping into those places with a bit of trepidation, we were met with warmth, not just towards us but also towards our request for solidarity. Because, as we learn so regularly on the field, solidarity begins with the touching of worlds, worlds that begin as strangers to each other and are then opened to be affected by one another.

W. has been pushed back 3 times now by the Croatian police. The last time they pushed him back his possessions were stripped from him and he was conned out of money by the taxi driver that returned him to Bihać. Every day we hear people’s experiences firsthand, we listen and we try to help in whatever little way we can.